Magnifying Nature’s Whispering

Taiwanese producer Judy Wu Chin-tai shares her passion for nature, indigenous recordings, and conservation in an interview with the editor-in-chief of Music Press Asia, Monica Tong.

Taiwanese producer Judy Wu Chin-tai shares her passion for nature, indigenous recordings, and conservation in an interview with the editor-in-chief of Music Press Asia, Monica Tong.

Judy Wu fulfills her role as an ambassador of nature, pledging us all for change and awareness on the subject of conservation not only for wildlife but also for the indigenous community worldwide. In this interview with Music Press Asia, she speaks of her passion for sound expressed by animals, tribal communities, the wind, and even cracklings of the glaciers.

PART I: INTRODUCTION

Hello Judy! It’s a pleasure to have you here at Music Press Asia. First of all congratulations on the release of your latest album ‘Nature’s Whispering’. In this project, you mentioned that you hope ‘to chronicle the here and now through creating music with the sound of nature’. Tell us why you think the title of the album strongly represents the objective of this project, especially in such crucial times in history.

The title conveys the meaning of a collection of soundscapes from wildlife and human beings classified under biophony[1], geophony[2], and anthrophony[3]. From our perspectives, it might not be whispering, however, on a larger scale – from the perspective of the Earth and the planet – these are whisperings. You can’t even hear it sometimes if you don’t pay attention. Rather incidentally, some of these sounds may have even probably disappeared in time; sounds we never knew existed before. So that is why I think is probably one of the main reasons why I wanted to create music using these recording clips.

You are philosophical about the music you create from nature, something that cannot be explained instantaneously.

Back then when I was still studying music in the United States, we have this core course, a music history class. There, I learned about all the different kinds of styles of music created within specific periods that have a lot to do with what happened to history. Just like music, art and whatever was going on during that time in the society play a part in influencing that period.

Although we would go into historical details on how things changed music, and how social situations influenced music and art forms. Never have I heard people discuss nature in depth. Perhaps, that was something people didn’t pay attention to, or perhaps the planet wasn’t in such a dire situation as now. But after the Industrial Revolution, the world started to change and economic growth was rapid. This can get more complicated to explain. A heavy topic nonetheless.

PART II: THE ALBUM ‘NATURE’S WHISPERING’

How did you select the sound and music for this album from the mass recording collection you’ve amassed over the last 20 years of your career?

Throughout the twenty-something years, I recorded a lot of sounds. But some of them have yet to be published, just as some of the stories have yet to be told. Of all the impactful and touching moments that I’ve been through, I feel that there is a need to share the stories behind these sounds. I’ve been a producer of wildlife and their music; in other words to serve them [wildlife] so that they can be the main character in my music.

Somolo Solo, the first track of the album, contains a sample of nearly lost traditional singing of the Tsou tribe, a track which you’ve recorded in 1994. Tell us more about the story which unfolded during the day of recording. What are the contents of their song and why do you believe that it is so important to keep their singing alive?

The Somolo Solo tune is an ancient tune passed down from their ancestors. It’s a way of communication, rather like ‘daily talk’. The people would improvise text to a specific tune to talk to each other. And so the historical significance of this tune lies in the fact that once they lose the language, especially among the younger generation, they will also have a hard time learning to sing the song again. You see, this is because the song is sung in the Tsou language.

Somolo Solo the name itself is meaningless just like a lot of other indigenous songs. These meaningless vocals are used in the melodies as a way to express their current state of mind.

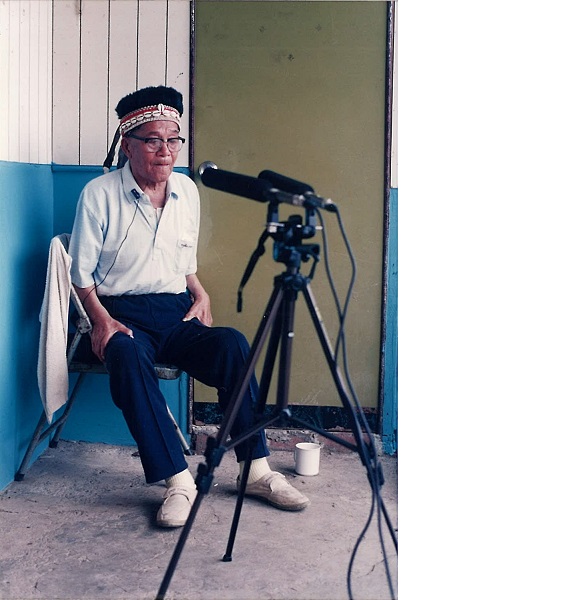

In 1994, those who were able to sing this song in my recording were between 70 and 90 years of age. I especially remember recording the singing of an old grandpa, who could have been nearly 100 years old then. He was so excited that he wouldn’t stop singing. The recording went well over 6 or 7 minutes; a duration apparently too much for his 70-year-old son to bear. We know well to stop recording from the hand signals of a son who thought too much singing may not be such a good idea after all.

After we finished recording, we inquired about the content of the lyrics and found no satisfying answer. The locals understood the first phrase as a welcome song, and that was the extent of what we’d found out. You see, the indigenous language does not have any written form. Although I believe that there are different ways of expression in ancient times, it is also a higher level of expression, somehow elegant, different from how we communicate today.

This recording was actually recorded on my first outpost assignment at Wind Music. We’d made plans to visit not only the Tsou tribe in the Alishan region in the central-southern region of Taiwan but also to record nature along the way. Back then I was only in my twenties and had just returned from studying in America. I must have felt quite unsure about not having seen a lot of the world. But even then, I was sure that the Tsou tune would definitely disappear if no recording was made.

[The Music of the Indigenous on Taiwan Island is produced by Professor Wu Rung-shun, and Judy worked as an assistant for Vol.6 (The Songs of the Tsou Tribe) in 1994.]

Tell us more about the story of the song recorded by the Massai tour guide in East Africa. How did you come about this recording and why is the emanyatta olorikan ceremony (celebrated every 15 years) play a part in telling the story for this album in particular?

In 2017, I went on a safari. That was how I met Sammy, the driver-guide. While most of the other drivers wore western-made uniforms, I was intrigued by his Massai traditional costume and long-stretched ear-lopes. My attention toward the animals was minimal compared to the attention and questions I had directed at Sammy that day. We’ve been keeping in touch regularly ever since.

I wanted to dedicate a song from the album to this special character. In the end, it was Sammy who had sent footage of the tribal ritual that celebrates the coming of age for his age group. Sammy doesn’t know how old he is and that alone had a huge impact on me. I realised that there are concepts of the modern world that we’d taken for granted – that we’ve forgotten about the diversity of our planet. Even on the same earth, there are people living in totally different ways, and Sammy’s story is just one of the many I’d like to share.

Sammy grew up in the bushes and never went to school. But he learned English, just as how he’d taught himself to drive and about photography. He is an amazing person, and indigenous too just like the ones I’ve met in the tribal communities here in Taiwan. Each of them has their own music and story to tell; a diversity that most people wouldn’t even pay attention to.

PART III: CONCLUSION

How is this album different from your past creative works?

It has been ten years since I last released an original composition album. And prior to that album, it was also a 10-year gap, so naturally, felt like I have a lot to say. As I was discussing the objective and contents of this new album with Billy, the album’s project manager, he came up with a great idea we could use. The pandemic has, in many ways, trapped and restricted travels and movements across borders. If only we could create something that would allow our audience to travel to nature; that music and sound from various countries I’ve visited would once again go beyond borders, even during the pandemic.

The hot topic of the era talks a lot about conservation just like what you have done in this album. Do you see yourself as an ambassador for nature?

I am, definitely! I was not before, you see. Before I started recording nature music, I wasn’t even paying attention to the environment. It has always been incredibly difficult to record clean sounds in the wilderness as man-made noises are everywhere. Human invasion in the wilderness is real.

How has a career recording sounds of nature changed your perspective of who you are?

For a period of time, I was kind of ashamed of being a human.

One day, I was given the assignment to record the sound of migrating birds on a wetland. Making sure that I am, naturally, as hidden and invisible as possible in their presence, I had to sit extremely still. More often than not, and because of the heavy equipment and tools that came along my little excursion, I’d scare these school of birds away, never to return again to the camped spot. It made me think long and hard about how to complete this task successfully. Strategically, I began to pack lesser tools that would be unnecessary for the trip. In their presence, I also began pretending like I am just like any other animal that chose to land on that particular wetland that day. Unsurprisingly, I managed to disturb a small school of birds. Their lift-offs sent them circling above my camp scouting for threats before considering landing again. After analysing a safe plan, sliding back onto the pond would just be the most natural behaviour. At that very moment, I locked eyes with their glare to realise that I’m no longer a threat.

Of the numerous times that I’d be recording in the wilderness, alone, I would think about people who’d choose to domesticate wildlife. In retrospect, I rather enjoy the idea that I’m being domesticated by wildlife.

Click here to listen or purchase Judy Wu’s album NATURE WHISPERING.

Reference:

[1]Biophony refers to the collective acoustic signatures generated by all sound-producing organisms in a given habitat at a given moment. It includes vocalizations that are used for conspecific communication in some cases.

[2]Geophony, from the Greek prefix, geo, meaning earth-related and sound, is a neologism used to describe one of three possible sonic components of a soundscape. It relates to the naturally occurring non-biological sounds coming from different types of habitats, whether marine or terrestrial.

[3]Anthrophony (uncountable, noun). Any sound produced by human beings or their creations.